Day 43: 23 August: Whitemen & Indians: frying fish at the illegal potlatch

August 24, 2008 by Harry,

Filed under Trip reports, Canada, Yukon

Hi all, apologies for not posting before, we were too busy cycling, getting fed by friendly Canadians, watching bears and visiting doctors. I wil write about all of that soon, but first as promised, our day in Champagne:

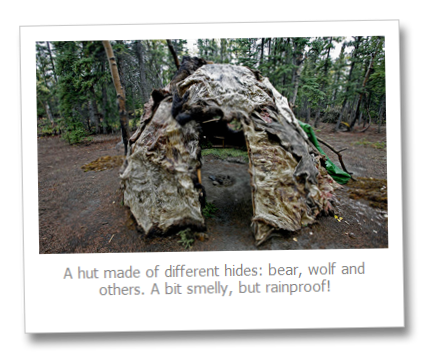

We woke up to a nice day, which means: no rain 🙂 Before heading out towards the seductions of Whitehorse, we decided to cycle around in Champagne, which appeared to be a ghost town. We spotted some good campsites near the community hall, wondering why our ‘hosts’ had not pointed these out. Just when we were turning around to start our trip towards Whitehorse, noticed some smoke coming out of a building. We checked it out and found a few ladies cooking in a large kitchen.

‘Do you want some breakfast?’ One asked.

Letmethink-yes!

‘Sit down, you can stay for the Potlatch.’

We had no idea what the Potlatch (often called Potluck) was, but we found out during this wonderful day. It was one year ago that one elder of the Champagne-Aishihik First nation had died. Now, one year later, a spirit house was built on her grave and all friends and family came together for the celebration of this occasion and to remember her.

So during the day a row of people came into the huge community hall, from very young to very old.. We were happy that we could help out during the day. I helped making al the tables and chairs ready for 200 persons and grilled several hundred of ‘Hooligans’: some small type of fish. Ivana helped serving the people, there were many courses. We got fed ourselves as well: from Moosejaw soup to fish eggs to salad and salmon. Ivana convinced teh shy children that she could turn them into animals by painting their faces. We talked with the elders as well as the younger generations. It was all great.

I spoke a while with Yoyo, one of the elders.

‘So you can tell your friends that you were with the Indians and that they all wore feathers and such’, Yoyo remarked.

I told him that that stereotype was not my impression of the First Nation people we had met so far. He looked at me, decided that I was good and started to talk about his past.

‘You know, the younger generation cannot speak our language anymore. I am one of the last ones to speak it. Our language is lower to the ground, closer to the earth. If I forgot my gloves near a tree in a big forest 60 miles away, I could explain a friend where to look for them in a few minutes. In the high speech, this is impossible’.

‘We were happy, but when the white people came, they took our children and put them in religious camps. They had to learn the bible and forget about all that our ancestors had taught them. Most came back broken, cut off from their traditions. Now slowly we get some rights back, but the connection with our past is gone forever…’

‘In our tradition, there is no hierarchy, no rich and poor. We share all things. Some people might have a better harvest, a better hunt or nowadays a better salary. We share all, so everybody can live well. This was forbidden in the Indian Act, as the missionaries said it was ‘non-Christian’ to have no ranks and to share everything…’

During the day the tables in the back were filled with all kinds of things: food, blankets, plastic stuff. It was a bit strange to see all that, but we found out that all items would be given away to the ‘Wolves’. The Indian ‘Band’ was divided in Crows (Ravens) and Wolves, an ancient way of preventing bloodlines to become too limited: a wolf can never marry another wolf etc.

One of the organizers, Ted, gave me a red ribbon and told me to wear it, I was an honorary wolf and therefore would participate in receiving gifts. One of the first things I received was a huge warm blanket. Very nice, but completely unpractical on a bike, so I asked if they could give it to somebody else who might need it more. One of the people in charge came to us and told us with a serious face that it was very impolite to refuse gifts at a potlatch. We got the hint and happily received heavy items, food and other things. In teh end we gave most of it away to some family members who seemed to need it more.

There was a young and very shy couple -of which I am not sure if their parents had kept to the Wolves/Crows code- that was incredible happy with all the gifts. At one point the young man and woman softly spoke a few words that for me summarizes a lot of the people of Alaska and the Yukon: “Great, now I do not have to go hunting for a week!’. ‘And we can invite all our friends and share this with them’, his girlfriend replied cheerfully…

One of the interesting things is that most relatives donated money. The received amounts were read aloud: Mr x has donated $5. Mr Y and family have donated $250. All donations were received with applause and ranged from $5 to $750. At the end of the day, the money was used to pay off the kitchen staff, for any other costs that had been made, and for the gifts. What was left, was handed out to all people, where the elderly and poorest clearly got their share first. They even donated $10 to me and as I was not allowed to refuse, we came out ahead on this day, but in many more ways than just financially…

Some background information about the Aishihik First nation & Potlatches:

Champagne and Aishihik First Nations

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Champagne and Aishihik First Nations is a First Nation in the Yukon Territory in Canada. Its original population centres were Champagne, Yukon and Aishihik, Yukon, but most of its citizens moved to Haines Junction, Yukon to take advantage of services offered there such as schools. The First Nation government has its main administrative offices there. Other settlements used included Klukshu, Yukon. Many also live in Whitehorse where the First Nation government has offices. The language originally spoken by the Champagne and Aishihik people was Southern Tutchone.

The Champagne and Aishihik First Nations was one of the first four First Nations to sign a land claims agreement in 1992. The First Nation is also pursuing a land claim in its traditional territory in the northwestern corner of British Columbia.

External links

- Champagne and Aishihik First Nations web site

- Government of Canada’s Department of Indian and Northern Affairs First Nation profile

From their website:

In 1993, after more than 20 years of negotiations, CAFN’s rights to the Yukon portion of its traditional lands and resources were finally confirmed with the signing of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Final Agreement between CAFN, the Government of Canada and the Government of Yukon. Land claim negotiations concerning the portion of CAFN territory within BC are as yet incomplete, but in the interim, an innovative and precedentsetting agreement between the BC government and CAFN has been reached which provides for joint management authority of the newly created Tatshenshini-Alsek Park.

The road to the Yukon Land Claim Agreement was a long and difficult one. Many Champagne and Aishihik members, beginning with the late Elijah Smith, provided creative leadership in initiating and negotiating an Umbrella Yukon Land Claim Agreement. Elijah organized the Yukon Native Brotherhood and, in 1973, he presented Together Today for our Children Tomorrow, a position paper on the Yukon comprehensive claim, to then Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau. CAFN was one of the first four Yukon First Nations to conclude their final agreements.

CAFN’s Dave Joe was the Chief Negotiator for the Council for Yukon Indians (now the Council of Yukon First Nations) was instrumental in completing the Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement. The late Harry Allen and Dorothy Wabisca, along with Chief Paul Birckel, were also key players in the successful negotiation of these groundbreaking agreements. CAFN’s Land Claim Agreement provides for the ownership of some 2,427 square kilometers of land. It also continues to provide guaranteed access to fish and wildlife resources. Most importantly, the agreement establishes the CAFN government as co-managers of all natural and cultural resources in its traditional territory. CAFN is now a full partner on the Kluane National Park Management Board, the Alsek Renewable Resources Council and has representation on numerous other regional and territorial boards that make recommendations on heritage, educational, environmental and economic issues. In addition, the self-government agreement provides CAFN with the power to enact laws on a wide range of matters affecting the rights of its citizens.

On September 17, 1998 the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations made history by passing three acts: the Income Tax Act, Fish and Wildlife Act, and the Traditional Pursuits Act. These acts became effective on January 1, 1999. A variety of municipal services, (housing, roads, water and sewer) as well as social services (health, nutrition, employment and training) are fully administered by the First Nations’ government. The Department of Lands and Resources, which also includes Heritage and Economic Development, manages CAFN’s traditional lands and integrates education and training of its citizens. CAFN has undergone radical change in the last 100 years. Not long ago, the Southern Tutchone people of this region lived as part of the land. Today, they are working on the establishment of their own government and CAFN is becoming the steward of its homeland as it builds a sustainable economy.

Wikipedia: excerpt from Indian Act:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Act

1885: Amended to prohibit religious ceremonies (such as potlatches)[6]

WikiPedia: Potlatch

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potlatch

A potlatch[1][2][3] is a festival ceremony practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in North America, along Pacific Northwest coast of the United States and the Canadian province of British Columbia. This includes Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Tsimshian[4], Nuu-chah-nulth,[5] Kwakwaka’wakw[6] and Coast Salish[7] cultures. The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning “to give away” or “a gift”. It is a vital part of indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest. It went through a history of rigorous ban by the Canadian government, and has been the study of many anthropologists.

The potlatch is a festival or ceremony practiced among Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. At these gatherings a family or hereditary leader hosts guests in their family’s house and hold a feast for their guests. The main purpose of the potlatch is the re-distribution and reciprocity of wealth.

During the event, different events take place, like either singing and dances, sometimes with masks or regalia, the barter of wealth through gifts, such as dried foods, sugar, flour, or other material things, and sometimes money. For many potlatches, spiritual ceremonies take place for different occasions. This is either through material wealth like foods and goods or immaterial things like songs, dances and such. For some cultures, like Kwakwaka’wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts genealogy and cultural wealth they possess. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures like the dzunukwa. Typically the potlatching is practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends.

Within it, hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, are observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods. Chief O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu’ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas, “We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, ‘Do as the Indian does?’ It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.”

Celebration of births, rites of passages, weddings, funerals, namings, and honoring of the deceased are some of the many forms the potlatch occurs under. Although protocol differs among the Indigenous nations, the potlatch will usually involve a feast, with music, dance, theatricality and spiritual ceremonies. The most sacred ceremonies are usually observed in the winter.

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, tribe, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch so as to present a very diverse presentation and meaning. The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for all different specific types of gatherings. Nonetheless, the main purpose has and still is the redistribution of wealth procured by families.

History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan [candle fish] oil or dried food), canoes, and slaves among the very wealthy, but otherwise not income-generating assets such as resource rights. The influx of manufactured trade goods such as blankets and sheet copper into the Pacific Northwest caused inflation in the potlatch in the late eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries. Some groups, such as the Kwakwaka’wakw, used the potlatch as an arena in which highly competitive contests of status took place. In rare cases, goods were actually destroyed after being received. The catastrophic mortalities due to introduced diseases laid many inherited ranks vacant or open to remote or dubious claim—providing they could be validated—with a suitable potlatch.[8]

The potlatch was a cultural practice much studied by ethnographers. “Potlatch is a festive event within a regional exchange system among tribes of the North pacific Coast of North America, including the Salish and Kwakiutl of Washington and British Columbia.”[citation needed] Sponsors of a potlatch give away many useful items such as food, blankets, worked ornamental mediums of exchange called “coppers”, and many other various items. In return, they earned prestige. To give a potlatch enhanced one’s reputation and validated social rank, the rank and requisite potlatch being proportional, both for the host and for the recipients by the gifts exchanged. Prestige increased with the lavishness of the potlatch, the value of the goods given away in it.

Potlatch ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1885[9] and the United States in the late nineteenth century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it “a worse than useless custom”[citation needed] that was seen as wasteful, unproductive which was not part of “civilized” values.[10]

The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was “by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.”[11] Thus in 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practice. The official legislation read, “Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the “Potlatch” or the Indian dance known as the “Tamanawas” is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in a jail or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.”

Eventually it became amended to be more inclusive as earlier discharged on technicalities. Legislation was then expanded to include guest who participated in the ceremony. The indigenous people were too large to police, and enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offense from criminal to summary, which meant ‘the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence.”[12]

Continuation

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, indigenous people now openly hold potlatch to commit to the restoring of their ancestors’ ways. Potlatch now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright.

See also

- Koha, a related concept among the Māori

- Kula ring, a similar concept in the Trobriand Islands (Oceania)

- Moka, another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Sepik Coast exchange, yet another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Guy Debord, French Situationist writer on the subject of potlatch and commodity reification.

- Gift economy

You might also like

|

|

|

|

|